Robbie's – Nice pub, shame about the pint

Plus the alchemist who invented spirits.

It’s a wintry Wednesday night and the barman has kindly changed the channel to put the football on for us. He clearly gets on with the regulars chatting away.

We’re in Robbies, an old-style corner pub on Leith Walk. It’s all in one room, with some more private snugs nestled in the corners. The tables are nicely spaced out, nobody’s packed in this fairly quiet evening.

The pub recently saw a bit of a refurbishment, which unfortunately saw the loss of its dartboard at the back – but it’s kept lots of its old memorabilia and plenty of character. This being Leith Walk, there are some nods to Hibs dotted around the place.

The walls are also adorned with framed etched mirrors displaying past Edinburgh brewers I’ve never heard of. It’s always surprising, and delightful, to see how many different names make up our brewing and distilling history. Hanging orb lamps and a grand old pendulum clock complete the look. It’s an impressive facsimile of an old-school Leith pub.

It reminds me of a couple of nearby pubs – Cask & Barrel and Mather’s on Broughton Street. They’re all traditionally decked out, largely male spaces with tellies showing sport.

The difference is that Robbie’s cask ale quality is a step down from its neighbours. I’m surprised to hear the local Camra branch has met there, because in my experience, it’s not exactly a real ale haven. Perhaps I’ve just been unlucky on multiple occasions. They have three casks on, but I decide to swerve them this round and stick to Guinness.

It’s a shame. One memorable pint on a busy night a while back was served in a hot glass – straight out of the dishwasher – rendering it pretty much undrinkable.

It would be nice if Robbie’s owners Caledonian Heritable (the people who run a number of venues in Edinburgh including The Bailie Bar, The Dome and Forresters Guild in Portobello) put a bit more care into the cask here. But if ale’s not your tipple, you’re in for a fine night.

Where is it?

Where next?

Luckily on Leith Walk, you have multiple options. Head towards central Edinburgh and stop off at The Windsor.

Or go the other way towards Leith and pop into The Harp & Castle.

The chaser – Divine Water

Scotch whisky makers are not happy with their English counterparts. There are plans to allow English distillers to use the term “single malt” for the first time.

Under the current rules, whisky can only be called “single malt” if it is mashed, fermented and distilled at the same site. Currently proposals would allow English distillers to call their product “single malt” if it is all distilled at the same site, but mashed and fermented elsewhere.

The Scotch Whisky Association told the BBC this would “remove the fundamental connection to place that single malt Scotch whisky has”. As a Scotch fan (albeit an English one) I tend to agree.

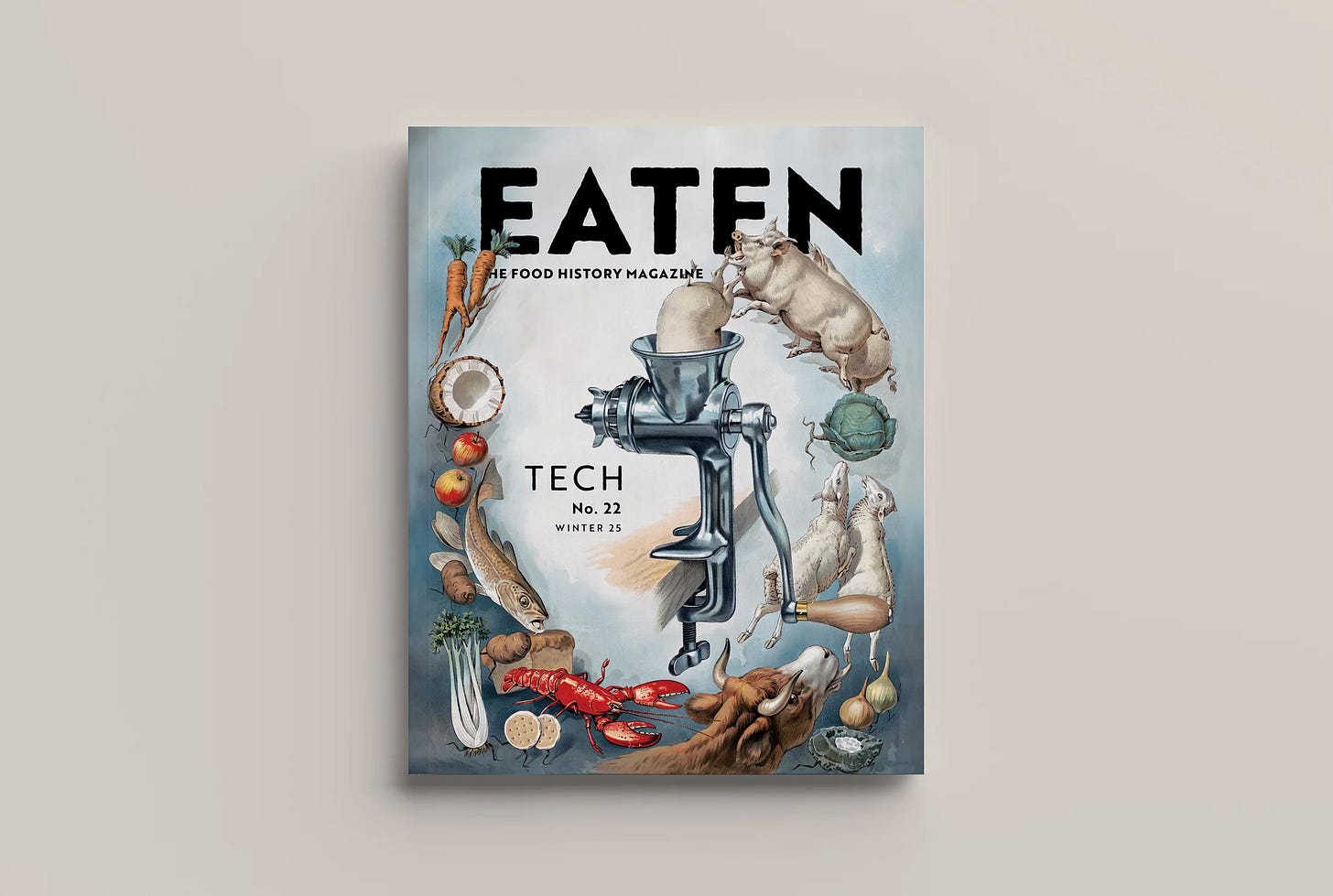

On the subject of distillation, I recently wrote a piece for Eaten, the history of food magazine, about the woman we have to thank for the whole process.

Maria the Jewess was an alchemist who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, nearly two thousand years ago. She was a prolific inventor, credited with designing dozens of pieces of apparatus, including the eponymous bain-marie.

But her most enduring invention was the still. A largely unchanged version of Maria’s design is the same one you’ll see in distilleries around the world today.

Maria wasn’t distilling in order to get drunk – she was distilling to try and get closer to God. Some would say the two pursuits are not so different.

The full article is only available in issue no. 22 of Eaten, which is available to buy online. But I’ve left a little extract for you below.

The divine art [alchemy] had two related missions. The first was the pursuit of a substance which could grant immortality. This wasn't an attempt to play God, but rather an attempt to make sense of Him. The second was transmutation—turning base metal into gold. Again, the goal was not a selfish one. If gold could be created out of other metals, it could prove that God had created everything from the same unknown substance, what Maria called the “All.” Her reasoning went like this: in the same way man nourished himself with food and drink to become one body, different substances could be put together to become another thing altogether—gold. “Invert nature,” she said, “and you will find that which you seek.”

Transmutation and immortality were not mutually exclusive goals. A common alchemical experiment, the distillation of eggs, shows the link between the two. On its second distillation, an egg produces a yellowish liquid. Could it be, pondered the alchemists, that the “yellowness” of the liquid was the same property that made gold yellow? If the egg distillate could be infused into a base metal, could it turn the metal into gold? The common belief at the time was that eggs contained pneuma, the breath of life. If this could be transmuted, it would mean the alchemists were one step closer to discovering the nature of the “All.”